It’s 6pm Friday and your employee is in your office in tears. She says she has far too much to do, hasn’t got enough support, and is exhausted. At home, her relationship is on the verge of breaking up.

You want to be an empathetic team leader, but you’re stretched to capacity yourself — so is your whole team. It looks like a bad case of burnout. Should you have seen it coming?

With burnout rates climbing, it’s an increasing challenge for leaders in a legal environment with rising demands and fewer resources. Even if your team is running smoothly, it’s likely one or more will be struggling due to other stress in their lives. In fact, it’s frequently a life issue (such as a relationship breakup, worries about kids or money) that tips a stressed employee into the red-light zone.

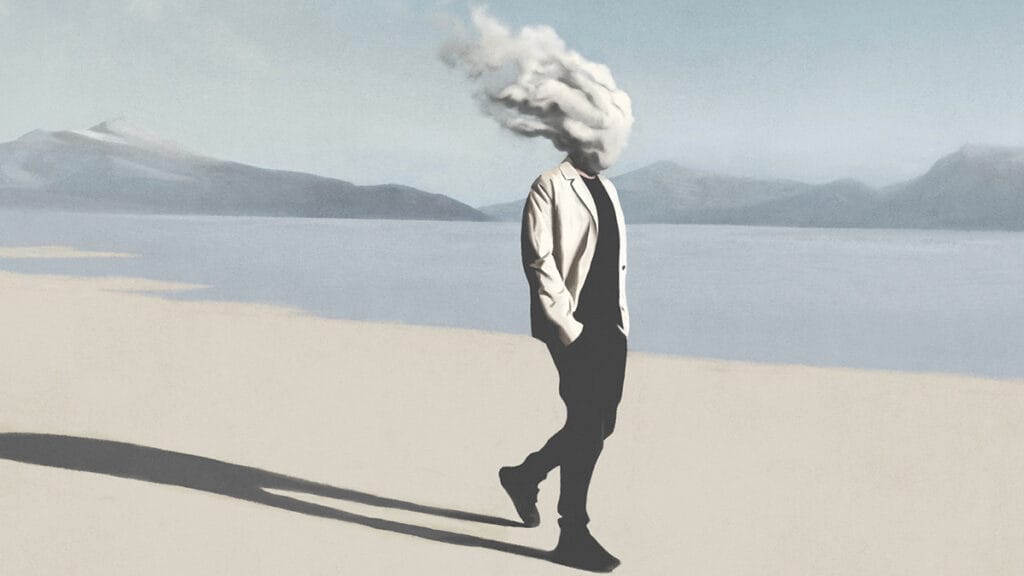

I call it the Perfect Storm — when work and life stress collide.

Burnout is the official term for chronic work stress. It can strike anyone, but overwhelming workloads, lack of clarity, a disconnect from values and a lack of support are the most common triggers.

The symptoms look similar to those of mild depression — sleep problems, fatigue and lethargy, low motivation, persistent low mood, irritability, exaggerated emotional responses, disinterest in favourite activities and people — nothing feels like fun anymore.

Because stigma still exists around mental health difficulties, many prefer a label of burnout over depression: it’s easier to tell your boss you are burnt out or highly stressed than you are mentally unwell.

Both burnout and depression are often not recognized until symptoms escalate, but the difference is that burnout tends to be (or should be) a more temporary condition. A decent break/rest, a change in the work environment or lifestyle, often lifts the symptoms.

A burnout diagnosis isn’t cause for panic. It’s just an alert system for mind and body: Hey, something needs to change here or I’m taking you down a more serious path.

Most experts agree on the three key warning signs:

(1) Physical and emotional exhaustion

(2) Feeling detached from, and cynical about, work and your contribution

(3) Falloff in performance. This is often the last one to show up; it’s surprising how long people can work at high levels when they are emotionally and physically run down.

Burnout is a reality in a stretched environment and team leaders can’t be expected to anticipate every case. But early intervention and reduction are good aims. Here are some tips to help.

Monitor workload — how many tasks are staff doing and is it a fair and reasonable workload?

Know what’s going on at home —life events are often the tipping point. If you understand your people’s lives, you’ll understand them. And the more they will appreciate you and support your leadership.

Provide clarity around roles — uncertainty around expectations is one of the most common complaints. Be clear and specific on what’s expected of them, including timelines.

Keep your door open — keep everyone up to date with what’s going on. Don’t spring surprises. Be available (within reason) to listen to their problems or provide other support, such as a mentor.

Allow autonomy where you can — this is why WFH and hybrid work have been so popular. When people feel they have some control over their lives, they are happier.

Make them feel valuable — genuine specific praise for their contribution fosters goodwill towards you and the company.

Encourage down time — everyone loves downtime but not everyone wants to socialize with the team. Try to match your offers of downtime with their preferences.

Model healthy habits — even if you have a huge capacity for work, show your team that you approach work (and life) in a healthy way.

Above all, check in on your work environment. You can’t control all that goes on in people’s lives, but you can promote healthy habits and a supportive workplace culture.